“That is something I’m not able to interview about because it is classified,” one potential source told me, and I was told much the same by another half dozen people.

I was trying to contact dolphin trainers who had worked in the U.S. Navy’s Marine Mammal Program, but I was having no luck whatsoever in finding someone willing to share. I also failed to get a call back from the Navy itself, but I can’t say that surprised me.

If you’ve never heard of the Navy’s Marine Mammal Program, then, well, you’re just like I was a week ago. Then I found a news story about how North Korea was training kamikaze dolphins and quickly got sucked into a rabbit hole about militarized dolphins. Not only did I find out that North Korea is likely training dolphins for real, but I also learned that a few other countries have been doing it for decades — including us! While some mission-specific information remains secretive, here’s what we know about the Navy’s dolphin program.

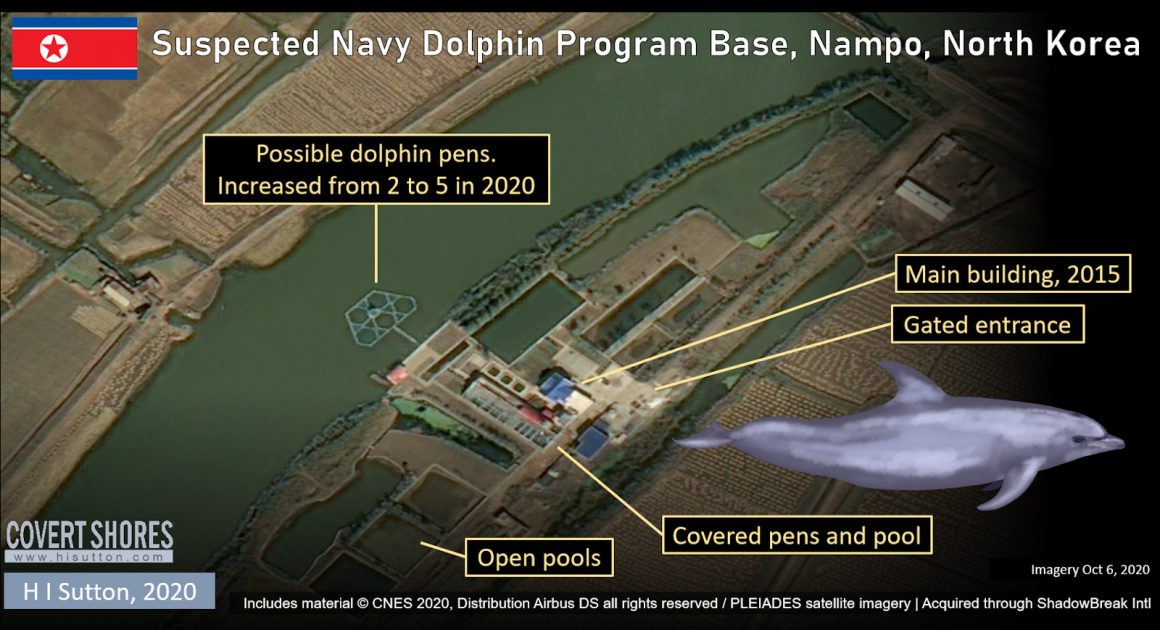

Starting with North Korea, who appear to be new to the dolphin army business, it seems that their program may have begun back in 2015, as U.S. Naval Institute News reports. Originally, satellite images showed two floating pens in a tributary of the Taedong River, but just this year, those pens increased to five and the size of the pens seems to suggest they’re specifically for dolphins (though it may also just be a fish farm).

What might North Korea use them for? Popular Mechanics explains that Russia previously used dolphins to “carry out kamikaze attacks against enemy ships, carrying explosive charges to their targets.” And because North Korea regularly provokes South Korea by attacking some of their ships, it’s not a stretch to think that they may also use dolphins to carry out similar missions.

Although, according to reporting by Slate, trained dolphins are — and always have been — extremely valuable, usually worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Because of this, they’d likely never be used in suicide missions; the life of a trained dolphin is just too valuable. Russian dolphins were used to plant explosives, though, in addition to their work detecting submarines, mines and even underwater enemy intruders.

The Russian program began in 1965 and in 1991, when the Soviet Union broke apart, it was inherited by Ukraine, as the dolphin training facilities were in Ukrainian waters. After that, some of these dolphins began to be used for therapy with children; the rest were sold to Iran in 2000 after Ukraine decided they were too expensive to keep. It’s unclear what became of those dolphins, though; since dolphins live for about 50 years, it’s possible that they’re still in Iran today.

In 2012, Ukraine decided to give the dolphin army thing another go, but two years later, when Russia stole Crimea, they got Ukraine’s dolphins as well. Since then, it seems that Russia’s dolphin force has been on the rise. In 2016, Russia’s military put out a contract to buy five dolphins with “perfect teeth” for military usage. In 2019, Norwegian fishermen found a Beluga whale with a harness on it that said “Equipment of St. Petersburg,” which made many believe that he was a Russian spy whale. Although, this text was in English, which might also mean it came from St. Petersburg, Florida. To this day, no one knows where the whale came from, but it seems that he has remained in Norway, where he occasionally pops up in the news for being super cute.

Although that beluga may not have been a Russian spy, a report from earlier this year states that, in 2018, Russia likely deployed dolphins in Syria during the Syrian civil war (which is still going on today). From September until December of 2018, dolphin pens were spotted at a dock occupied by Russians. “The dolphins would likely be used to counter enemy divers who might try to sabotage ships in the port. The marine mammals might also be used to retrieve objects from the seafloor or to perform intelligence missions,” an article in Forbes explains.

By now it’s clear that Russia has resumed its 55-year-old program, but despite its longevity, the Russians weren’t the first to utilize dolphins in this way — that distinction belongs to the U.S. It began back in 1959, when the U.S. Navy began studying dolphins for inspiration in designing new torpedoes and submarines. During their research, they realized just how trainable dolphins were. As such, they started training dolphins for a variety of missions, including locating mines and flagging unauthorized divers. Beginning in 1965, dolphins were used during the Vietnam War to prevent enemy divers from attacking a pier that housed American ammunition. They later had a similar role in the Persian Gulf in the late 1980s.

After the Cold War ended, America downsized the program, and in 1992, it became declassified, although some of its operations still remain secretive, as I discovered myself recently. Despite my multitude of rejections however, I did eventually find one person involved who was open to discussing the program. Lynsie, who was a civilian intern with the program from 2011 to 2012, tells me, “The interns help with the daily feeding and the cleaning with the dolphins and sea lions. We make sure those things happen so that the program can flow smoothly.”

To offer a bit of what the program looks like, Lynsie says that there are four areas. “There’s the veterinary team, the breeding team, the research team and the military team. The breeding program focuses on the mamas and the babies and any dolphins that may be pregnant. On the research side, that’s where they test how noise influences how the dolphins need to perform — like, if there’s a big ship nearby, they’re making sure the dolphins can still hear what they need to hear. Then there’s the training program and that’s more on the military side of things with the Navy. That’s where they train them to find mines and bombs underwater. Then the veterinary team tends to the medical needs of the animals.”

When getting into more detail about the military side of things, Lynsie says that the dolphins are trained much the way you’d train a dog. “You can train a dog to fetch and you can train a dog to find certain people based upon their scent, and this is similar. You start out simple, so the dolphins can start by finding something on the floor of where they live, and if they can find that, they get positive reinforcement. Also, they train them to jump out of the water, and eventually that leads to them learning how to jump into a boat so that they can be brought out to the open ocean for more in-depth training out there. Then you can just go deeper and deeper and deeper with them.”

This training eventually allows the dolphins to perform the tasks that really get to the heart of the whole program, as there are some things that dolphins can do that humans just can’t. For one, they can dive much deeper than humans and they can retrieve things much more quickly. They also have excellent hearing and vision underwater, which makes them better at detecting things than even the most advanced underwater drones.

Since the program has become public knowledge, some animal rights activists have argued that the pens the dolphins are kept in are too small, and several observers felt that some sick dolphins were being kept alive simply to train medical personnel, when euthanization would have been more humane. Also, more generally, they have cited the program itself as broadly immoral.

Lynsie understands the concerns people have for the animals, but insists that the animals are well cared for. “They treat the dolphins as if they’re a part of the team,” she explains. “Just like the dogs that look for bombs — soldiers with dogs treat those dogs like family, and it’s the same thing with the Marine Mammal Program. If you’re training them, you know them all by name and you’re taking care of them every day. You care about them, so they’re not just some tool to be used.”

To counter the dog comparison — which others have made before — animal advocates have argued that the domestication of dogs makes their training more acceptable, whereas dolphins are still wild animals that need more space and freedom than any enclosure could afford.

I totally respect and understand this argument — no dolphin, or any animal, really, belongs in a cage. That said, if another headline pops up talking about how “kamikaze dolphins” are working in the interests of an evil dictator like Kim Jong-un, I’m going to feel slightly safer knowing that we have our own military dolphins at the ready.